Walk into almost any gym in America, and you’ll see the same scene: people cranking out sit-ups, Roman-chair variations, leg raises, twisting under load, and using machines that bend and rotate the spine through huge ranges of motion — all in the name of “core training.”

I get it. I did every one of those exercises for years. It’s what we all saw growing up, and it felt like core work.

But after decades of battling my own back issues — and diving into the research of Dr. Stuart McGill (one of the world’s leading spine experts), Michael Boyle (one of the most respected strength coaches of the last 40 years), and Dr. Greg Rose of the Titleist Performance Institute (TPI – the gold standard of fitness for professional golf) — something became crystal clear:

Your core isn’t built to move your spine. It’s built to protect and stabilize it.

That one shift changes everything. And if that feels upside-down compared to what you’ve always seen on gym floors, stick with me. Once you understand how the spine is built — and what the top coaches in the world now teach — everything starts to make perfect sense.

The Coat Hanger Principle: Your Spine Only Has So Many “Bends”

Here’s the analogy I use with clients:

Your spine is like a wire coat hanger.

You can bend that coat hanger out of shape and back again once or twice — no problem.

But if you bend it back and forth repeatedly… eventually the metal fatigues and snaps.

Your spinal discs behave the same way.

Dr. Stuart McGill, the world’s leading spine researcher, has spent more than 30 years showing that:

- The discs can tolerate some flexion, extension, and rotation.

- But repetitive, loaded, high-amplitude bending cycles dramatically increase disc wear

- And everyone has a finite number of bending cycles before the tissue starts to break down

Now think about daily life:

Do you do 25 sit-ups during your commute?

40 leg raises at your desk?

50 Russian twists while cooking dinner?

Deep flexion and extension cycles over and over again?

Of course not.

The only place this kind of spinal bending happens is in the gym — not because the spine was designed for it, but because we were taught to train this way.

Your spine can move — otherwise you’d walk around like you had a two-by-four strapped to your back. But the ability to move doesn’t mean an unlimited capacity for repeated bending under load.

Just like the coat hanger, everyone has a limit. Some people can tolerate thousands of flexion cycles. Others tolerate far fewer.

But no one has unlimited reps.

How Your Spine Is Actually Designed to Move

The structure of the spine tells you exactly how it wants to move. The body leaves clues, and when you understand its design, everything becomes obvious.

Cervical Spine (Neck)

- Smallest vertebrae

- Built for lots of mobility

- Plenty of rotation and flexion/extension

Thoracic Spine (Mid/Upper Back)

- Medium-sized vertebrae

- Built for rotation

- This is where golfers, tennis players, pitchers, and quarterbacks generate turn and power

Lumbar Spine (Low Back)

- Largest, thickest vertebrae

- Built for load-bearing and stability, not twisting

- Only 1–3° of rotation per segment, and roughly 10–13° total

This is precisely what TPI co-founder Dr. Greg Rose teaches every day. The best rotational athletes in the world don’t twist from the lumbar spine — they rotate from the hips and thoracic spine while keeping the low back braced and stable.

And when you combine Rose’s work with the research of Dr. Stuart McGill and the coaching principles of Michael Boyle, the message is unified and unmistakable:

The lumbar spine stabilizes.

The thoracic spine and hips rotate.

Core muscles are stabilizers, not movers.

Why Sit-Ups & Leg Raises Aren’t Core Exercises (And Why They Stress the Spine)

This is the part that blindsides most people.

Sit-ups, leg raises, V-ups, flutter kicks, hanging knee raises, and Roman-chair sit-ups feel like ab exercises…

…but biomechanically?

They’re hip flexor exercises — not core exercises.

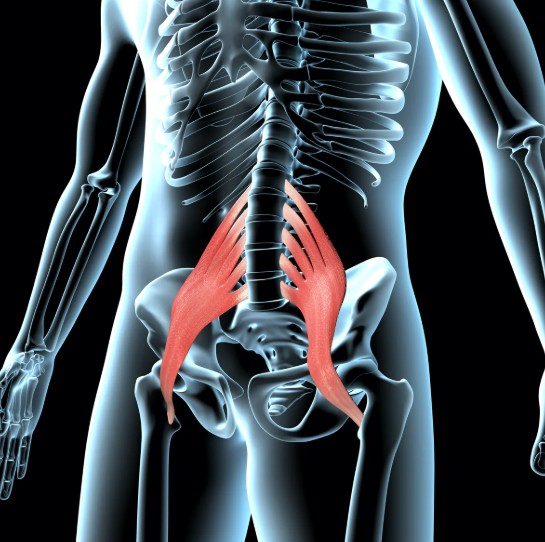

The Main Culprit: The Psoas

The psoas is the body’s strongest hip flexor, and it:

- Attaches directly to all five lumbar vertebrae

- Runs down through the pelvis

- Anchors into the femur

- Its job: hip flexion — raising your thigh toward your torso

So every time you perform a sit-up or leg raise, the psoas contracts and pulls on the lumbar spine with every single rep.

That creates:

- Compression

- Shear

- Repeated stress cycles

- Disc wear and eventual breakdown

And when you combine this with the coat hanger principle — the idea that your spine can only tolerate so many loaded bending cycles — the risk becomes obvious.

This is precisely why both Dr. Stuart McGill and Michael Boyle removed sit-ups and leg-raise variations from their coaching systems.

The Roman Chair / Decline Sit-Up: The Worst of the Worst

This variation is especially problematic because:

- Your legs are locked in (guaranteeing hip-flexor dominance)

- The decline angle multiplies the load

- The lumbar spine gets yanked into deep flexion under resistance

Boyle and McGill both consider the Roman-chair/decline sit-up one of the most spine-unfriendly exercises in the entire gym. It feels hardcore. But the spine pays the price.

Why I Don’t Program Leg-Raise Variations

Because the risk-to-reward ratio just isn’t worth it.

The only movement in this category I’ll occasionally use is the stability ball jackknife — and even then:

- You’re in a plank

- The load is horizontal

- And the lumbar spine stays neutral and protected

That’s core training. Not spinal bending.

THE GHR SIT-UP:

ONE OF THE MOST SPINE-STRESSING MOVEMENTS IN THE GYM

This one deserves its own spotlight because it’s not as common, but when someone does it, the lumbar spine is under enormous load.

Here’s what the movement looks like when done on the glute-ham raise:

Why this variation is even MORE dangerous than the Roman chair:

1. The pelvis is locked down solid.

Meaning: The spine is forced to bend — no sharing, no dissipation.

2. The torso starts horizontal or BELOW horizontal.

This dramatically increases the stress on the spine during flexion and extension.

3. The lever arm is enormous.

The farther your shoulders are from your hips, the more load is placed on the spine.

4. Hip flexors dominate even more intensely.

The psoas is pulling HARD on the lumbar vertebrae with no relief.

5. There is zero real-world or sport carryover.

No movement in life or sport mimics this pattern.

Stuart McGill would immediately flag this as a generator of spine-stress cycles.

Michael Boyle would never program this.

Dr. Greg Rose would label it a rotational/extension disaster for golfers.

Simply put: This variation is one of the harshest lumbar-flexion movements in any gym.

Gym Equipment vs. Human Design

(A Gentle Word About Rotation & Low-Back Machines)

Most gyms — including mine — have two very common pieces of equipment:

- Rotational torso machines (where the upper body stays fixed and the lower body twists against a weight stack)

- Seated lumbar extension machines (where you sit upright and extend backward against a pad across the upper back)

These machines aren’t “bad,” and people certainly aren’t using them with bad intentions. They’re simply built on an older understanding of how the core works.

But here’s what McGill, Boyle, and TPI’s Dr. Greg Rose all teach:

- The lumbar spine is not designed for repeated rotation under load

- The lumbar spine is not designed for loaded extension cycles

- Neither movement reflects functional human biomechanics

Rotation and extension absolutely occur in the body — but not the way these machines encourage them.

A Better Way to Train the Core

Instead of forcing the lower back to twist or extend under load, train the core the way it was designed to function:

To resist movement, not produce it.

That means building stability, stiffness, and control — not bending, cranking, or twisting the spine against a weight stack.

Think of these machines the same way you’d think of isolation exercises: they’re there, you can use them, but they’re not the most effective or spine-friendly way to build real core strength.

So What Should Core Training Actually Look Like?

(According to McGill, Boyle, and TPI)

Real core training isn’t about bending, twisting, or flexing the spine — it’s about resisting those motions.

That’s how the core actually functions in life, sport, and human performance.

Anti-Rotation (Resisting Twist)

- Pallof press

- Anti-rotation holds

- Split-stance cable holds

- Single-arm carries

Anti-Extension (Resisting Arching)

- Dead bug

- Ball plank

- TRX fallouts

- Tall-kneeling press-outs

Anti-Lateral Flexion (Resisting Side Bend)

- Suitcase carry

- Side plank

- Offset marches

Hip-Driven Rotation (Where Rotation Should Come From)

(TPI-style rotational training)

- Thoracic rotation drills

- Cable chop/lift patterns

- Medicine ball throws driven by the hips

- TPI rotational screens and power exercises

McGill’s Only Approved “Crunch”: The Modified Curl-Up

Minimal spinal motion.

Maximal abdominal activation.

The neutral spine was maintained throughout.

It’s the safest and most effective “true ab exercise” for training the abdominal wall without compromising the lumbar spine.

Core Training Sample Exercises:

THE TAKEAWAY:

Protect the Coat Hanger. Train With Design.

Your spine is one of the most remarkable engineering feats in the human body — resilient, brilliant, and built with purpose.

But even the best designs have limits.

- The lumbar spine resists excessive bending and twisting

- Hips rotate

- Thoracic spine turns

- Core muscles resist motion — they don’t create it

Excessive bending, twisting, or loaded flexion cycles wear down the discs over time. But when you train according to your body’s design, something powerful happens:

You gain strength.

You gain durability.

You gain longevity and freedom from pain.

Honor that design, and your spine will take care of you for decades.

Ignore it, and — just like that coat hanger — eventually the metal fatigues.

Your body is too valuable for that.

Train smarter.

Train safer.

Train stronger.

Train according to design.

Leave a comment