What you don’t know can hurt you in every aspect of life—but especially in the gym.

As a professional coach, one of the most dangerous scenarios I see is this: a well‑built man or woman performing an exercise, a newer lifter watching, and a quiet assumption forming—they look great, so they must know what they’re doing. Therefore, the exercise must be suitable for everyone.

Unfortunately, that assumption gets people hurt.

I’ve heard more than one elite strength coach say that many high‑level athletes make progress despite what they do, not because of it. Superior genetics, years of adaptation, and relentless consistency allow them to “get away with murder.” Their program design may be inefficient—or in some cases, outright dangerous—but their bodies tolerate it longer than most.

The average gym‑goer does not have that luxury.

A Conversation That Sparked This Post

Just last week, I engaged one of our members about a core exercise he performs weekly. I had recently shared a post on core training with him and jokingly said, “You must not have read my blog—you’re still doing that exercise.”

He replied that he had read it, but he’d been doing the movement for years without any issues.

That comment inspired this post.

Just because you haven’t experienced pain doesn’t mean damage isn’t being done.

In his case, the issue wasn’t immediate pain—it was posture. Tight hip flexors were affecting his squat mechanics, putting his lumbar spine at risk. That risk didn’t show up overnight. It accumulated quietly, reinforced by a movement pattern he’d repeated for years.

My goal wasn’t to criticize him. It was to educate him—and help him avoid a future injury he wouldn’t see coming.

Forty Years in the Gym: A Personal Perspective

I started lifting at 15. I’ll turn 58 in a couple of weeks. That’s more than 40 years of consistent strength training with very few breaks. Aside from short interruptions for skiing or, most recently, a two‑week layoff following hernia surgery in August of 2025, lifting has been a constant in my life.

On the positive side, I’m in excellent shape for my age, and I plan to keep lifting and setting an example until the good Lord takes me home.

On the other hand, four decades of training have taken a toll on my joints. If I could do it over again, I would have been far more intentional about load management, exercise selection, and recovery.

My first major wake‑up call came when I tore the meniscus in my left knee.

There was no warning. One moment, I felt like Superman. The next, it felt like a rubber band snapped inside my knee. The pain wasn’t a ten—it was a fifteen.

That injury didn’t come from a single bad step or freak accident. It was years of accumulated stress. The step‑ups I was performing that day weren’t the cause—they were simply the final straw.

At the time, I was using excessive load and an excessive step height. Today, as a coach, I would never allow a client to train that way. I now prioritize perfect form, controlled ranges of motion, moderate loads, and higher reps.

Four years later, in 2014, I tore my left biceps out of my shoulder—again, without warning. Two years after that, an MRI revealed multiple rotator cuff tears and a biceps tendon fraying “like a rope.”

I had no idea the damage was there.

And that’s the point.

The Compound Effect—For Better or Worse

Albert Einstein famously called compound interest the eighth wonder of the world. When applied wisely, it works in your favor. Applied poorly, it works just as powerfully against you.

I first heard a heartbreaking example of the negative compound effect from Darren Hardy, shared through the story of Tony Gwynn.

Tony Gwynn—one of the greatest hitters in baseball history—chewed tobacco for years. The damage accumulated silently. When the diagnosis finally came, it was too late.

The compound effect can fake you out. If the first cigarette caused lung cancer, no one would smoke a second one. If the first bad rep caused immediate injury, no one would repeat it.

But that’s not how it works.

Damage often builds quietly—until it doesn’t.

Exercises That Deserve a Second Look

With that background, here are several exercises I commonly see performed that warrant serious reconsideration—not because people are careless, but because they simply don’t know the risk.

Curtsy Reverse Lunge

In my experience, this is almost exclusively a female‑performed exercise. I understand the intent—glutes, stability, variety—but the cost far outweighs the benefit.

The knee is designed primarily as a hinge joint. It tolerates flexion and extension well. What it does not tolerate well is excessive rotational and lateral torque under load.

The curtsy reverse lunge places the knee in a compromised position, combining rotation, valgus stress, and load—all at once. Over time, this can irritate the meniscus and strain supporting ligaments.

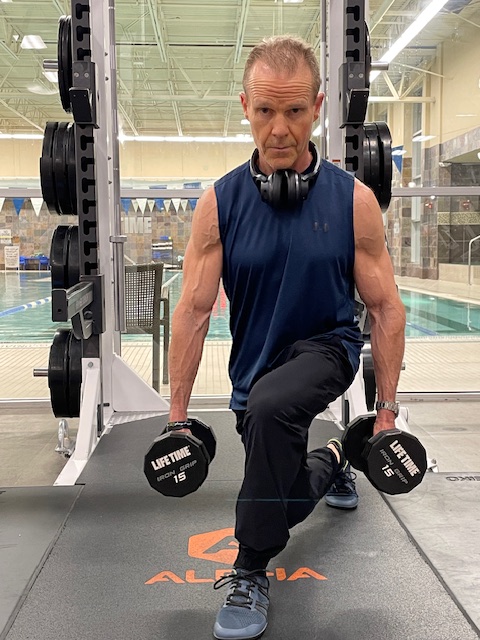

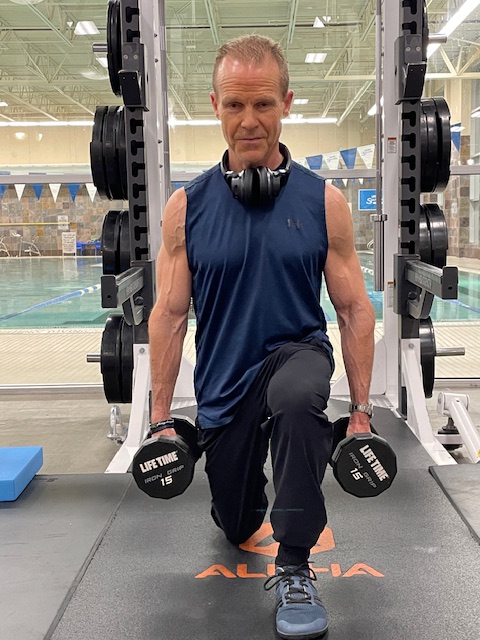

A standard reverse lunge—performed straight back—with dumbbells or a barbell provides all the quad and glute development you need without placing the knee at unnecessary risk.

Rear‑Foot Elevated Split Squat on a Standard Bench

A standard gym bench is roughly 18 inches high. That height is not based on biomechanics—it’s an industry standard.

In practice, you need to be around 6 feet tall with long femurs and excellent hip mobility to use that height without compromising form.

Most people aren’t.

When the rear foot is too high, the pelvis tips forward, the working leg loses range of motion, and excessive torque shifts to the hip flexor, groin, and lumbar spine.

For years, I instinctively elevated my front foot to offset this—because at 5’6”, it simply didn’t feel right otherwise.

A better solution is more straightforward: lower the rear‑foot elevation. A 4–8 inch platform allows a full range of motion, better balance, and dramatically less joint stress. This approach aligns with what Charles Poliquin taught long before this exercise became trendy.

Step‑Ups to Excessive Heights

Step‑ups already place a significant load on the knee. When you increase the box height—and then add heavy weight—you magnify that stress exponentially.

I recently saw a member performing step‑ups to a 24‑inch plyometric box. Even for tall individuals, that hip‑to‑knee angle is far beyond what I allow with my clients.

I prefer platforms that keep the hip‑to‑knee angle around 15–20 degrees. Combined with moderate loads and higher reps, this builds strength while protecting the knee.

Sissy Squats and Artificial Squat Positions

At the bottom of a well‑performed squat, the angle of the shin should roughly mirror the angle of the torso. This creates balance and distributes force safely through the joints.

Sissy squats exaggerate forward knee travel under load, placing extreme stress on the patellar tendon and knee joint.

The opposite extreme—often seen on Smith machines—is walking the feet far forward, making the shins vertical. This shifts excessive load exponentially to the lumbar spine.

Neither extreme is worth it.

A simple corrective drill: perform a bodyweight squat, hold the bottom position, and note your balance and knee position. Then replicate that setup with an external load.

Quarter Squats with Excessive Weight

Partial squats allow people to move far more weight than they can control through a full range of motion. The problem? Compressive forces on the lumbar spine skyrocket.

Unless you’re a competitive powerlifter addressing a specific range of motion, full‑range squats with moderate loads are far safer—and more effective for long‑term progress.

The Takeaway

Just because you don’t perceive damage being done doesn’t mean it isn’t happening.

Pain is often the last signal, not the first.

My role as a coach is not to chase trends or impress anyone—it’s to help my clients train safely, effectively, and for life.

If you want help evaluating your exercise selection, improving your form, or training in a way that protects your joints long‑term, I’d be honored to help.

Reach out via “Work with Kelly” Get coached. Your future body will thank you.

Leave a comment