You can’t afford to miss workouts. You can’t afford to miss workouts. As I’m writing this, it’s October 2025. Let’s roll back the calendar to spring 2024. One of my best clients, Phil Overton, began discussing a book he had purchased on longevity, titled “Outlive” by Peter Attia, M.D.

Dr. Attia is a cancer surgeon by training at Johns Hopkins. His undergraduate degree is in engineering, and he’s simply brilliant. But his current practice is not based on oncology; it’s centered on longevity. From his book, one of the first things Phil shared at the time didn’t seem right at first.

According to Attia, by age 75, your ability to regain lost muscle mass and strength after an injury or an extended absence from strength training declines significantly. If you fall and break a hip, or have a hip or knee replacement, or even a shoulder replacement, the muscle you lose during that inevitable downtime, you’re not getting it all back.

And for the record, I’ve seen all of those injuries happen to members at my club over the past seven and a half years. You have to protect against injury at all costs. And it’s not like everything is sunshine and roses up until age 75.

I’m a shadow of what I was just 13 years ago. I’ve had knee, shoulder, and hernia surgeries, plus a torn biceps that wasn’t repaired. That’s not even counting my first knee surgery in 2010. None of these injuries were planned or expected, but they happened — and the adverse effects on my muscle mass and strength have been significant.

The truth is, the decline doesn’t start at 75. The aging process begins much earlier. You should do everything possible to ensure your best chance of aging gracefully. The “big rocks” of longevity include exercise, nutrition, recovery (encompassing sleep and stress management), regular medical check-ups, and emotional well-being. While the details are beyond the scope of this post, I’ll include a link at the end to another article I recently published that explores those pillars in depth.

Strength training and cardiovascular workouts should each be done at least two days a week, period. If you’re not willing to invest a few hours a week into exercise, you’re not taking your health seriously, and you’re going to be in for a rude awakening when you hit your late 50s, 60s, and 70s.

You must also protect yourself from injury at all costs. Your body will lose strength and muscle mass in as little as 10 days of missed workouts. I have clients who go on vacation regularly — and I’m all for it. Everyone deserves downtime. But once you’re past 50, you don’t have the luxury of skipping workouts just because you’re away from home.

Most hotels and resorts offer fitness facilities, and if your travels don’t provide access to a gym, resistance bands are a great option. Give me a willing client with a set of bands, and I can guarantee a great workout with no formal equipment. It’s all a matter of discipline and mindset.

In September 2012, at around 150 pounds, I set my personal best with the trap bar deadlift — 340 pounds for four reps. Before that, I routinely trained with over 300 pounds. That was 13 years ago.

Then, in September 2014, the wheels began to come off. I tore the long head of my left biceps out of my shoulder. I was doing dumbbell curls when I watched, in horror, as the tendon tore and the muscle knotted up just above the bend in my arm. I left the gym in shock, already worrying about surgery.

I knew I needed surgery. But I had just started a new job and took a risk by not paying for COBRA insurance. By the time my new insurance took effect, my surgeon told me the odds of a successful surgery were only fifty-fifty due to scarring. He advised against surgery — and in hindsight, I wish I had risked it. My shoulder and arm still bother me to this day. It took months to return to regular lifting, and I lost both size and strength. My body had been warning me with shoulder and upper-back pain for weeks, but I ignored it.

In January of 2016, my right shoulder pain became unbearable. It hurt to put on a dress shirt or jacket. I learned my lesson and went to see Dr. Burns, who had repaired my knee back in 2010. The MRI showed multiple rotator cuff tears and a fraying biceps tendon. Dr. Burns said if he didn’t fix it, it would rupture just like my left one.

This was by far the toughest of all my surgeries. I wore a sling for six weeks and went through fourteen weeks of physical therapy. Even though I was back in the gym using my one good arm and legs a week later, it was months before I could train normally again. It was Thanksgiving before I attempted deadlifts, and in that eight-month absence from my favorite lift, my strength plummeted. Furthermore, my body weight dropped to the low to mid-140s.

Fast forward to spring 2018. I transitioned from a sales career to a full-time career in fitness. During my sales years, I lifted weights consistently four to five days a week and did cardio one to two days a week. However, I spent most of my time sitting in my office, my car, or at client sites. My daily steps were a fraction of what they are today.

Now, I average 11,000–12,000 steps per day — four to five miles — plus my personal workouts and client sessions. My activity level has never been higher. Ironically, ever since starting at Lifetime, I’ve progressively lost weight. Despite rarely missing workouts and eating clean, I failed to offset my high energy output with enough calories. My body doesn’t recover like it once did, and age plays a role. If this can happen to me, how much more at risk is the average person who doesn’t train consistently?

Before my knee surgery in May 2024, I had rebuilt to 150 pounds and was deadlifting 240–250 pounds. A year and a half later, I still haven’t gone over 225 — and now, after hernia surgery in August 2025, it’ll be even lower. I’ve had the hernia for years, but the fear of downtime kept me from addressing it.

The surgery went well, and I’m one month away from full clearance. I returned to light lifting two weeks post-op, but it didn’t maintain my strength. I only lost a few pounds, but several key lifts are down 10–20 pounds. I’m not giving up — but time and injury history aren’t on my side.

If you’d asked me back in 2009 whether I’d have four major surgeries (and a fifth that should’ve been done) by age 57, I’d have said “no way.” And yet, here I am — smaller, weaker, but wiser. I’m sharing this to help you avoid the same fate.

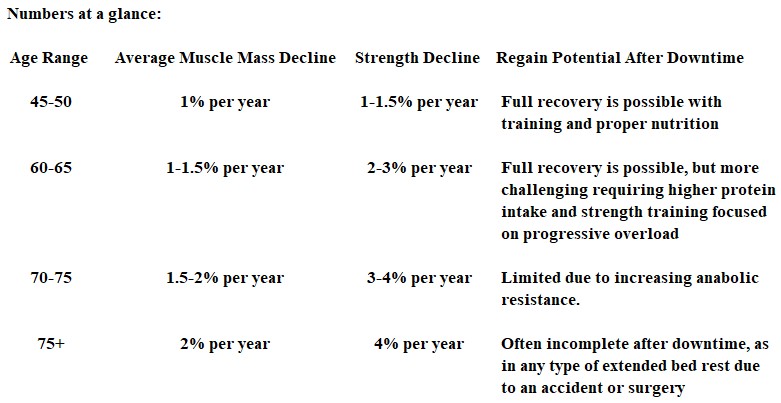

To further emphasize the impact of the aging process on muscle mass and strength, I would like to provide some statistics that may serve as a wake-up call if you’ve been neglecting exercise, especially strength training.

Muscle mass naturally declines with age, and the general trajectory, starting in the 30s and 40s for men and women, is to lose approximately 1% of muscle mass per year unless countered by resistance training.

Strength declines faster than mass, typically at a rate of 1.5 to 3% per year after the age of 50. By the age of 70 to 75, the average person has lost 25 to 30% of their muscle mass compared to their 30s, and strength loss can be as high as 40% or more.

Men tend to start with higher absolute muscle mass, but both sexes lose muscle at similar relative rates. Women experience a sharper drop around menopause due to estrogen decline, which accelerates sarcopenia and bone loss. After the age of 70, women may experience a steeper proportional decline compared to men.

The inability to regain lost muscle with advancing age is directly tied to anabolic resistance. This is where Dr. Attia’s statement regarding the significance of age 75 comes in. The biological reasons include hormonal shifts of testosterone, estrogen, growth hormone, and IGF-1; further, mitochondrial decline, reduced satellite cell activity, and systemic inflammation all play a role.

After the age of 50, the muscle protein synthesis (MPS) response to exercise and protein intake is 20-30% blunted compared to that of young adults. After the age of 65 to 70, this anabolic resistance worsened. It requires higher doses of protein, approximately 0.4 grams per kilogram per meal, or roughly 30 to 40 grams, and a higher training stimulus to achieve the same effect.

After age 75, the decline accelerates sharply. Suppose an older adult is immobilized, for example, due to a hip fracture or joint replacement. In that case, they can lose 2 pounds or more of lean tissue in just 10 days; regaining it is challenging, and in many cases, it is incomplete. Clinical data show that 50% of adults over 75 who suffer a hip fracture never return to pre-fracture mobility, primarily due to the inability to rebuild muscle.

At 57, my biggest takeaways are that it’s harder to gain or regain muscle mass compared to your 20s, 30s, and 40s, but you’re still in a zone where training and nutrition can yield results. Studies show that men in their 50s and 60s can still build lean muscle mass with consistent resistance training, adequate protein intake, and proper recovery.

The real fight is against the acceleration that occurs after the age of 70-75. Building as much strength and muscle as possible now is essentially your retirement savings account for resilience, protecting you against muscle loss and fall risk. There’s a direct correlation between the loss of lean muscle, sarcopenia, and an increased risk of falls.

Sarcopenia’s prevalence is roughly 10-15% in adults in their 60s, and 25-40% of adults in their 80s. People with Sarcopenia have a two to three times higher risk of falls and fractures compared to age-matched peers with preserved muscle mass. When comparing strength versus mass, lower leg strength, including the quadriceps, gluteals, and calves, is the single best predictor of fall risk, more so than total muscle mass alone. Muscle weakness is associated with slower gait, poor balance, and a decreased ability to catch yourself, which increases the risk of falls with age.

Falls are the sentinel event in aging. One in four adults over 65 falls each year, and falls are the leading cause of injury-related hospitalizations in older adults. Hip fractures are the most feared. 300,000 Americans 65 and over are hospitalized annually with hip fractures. Women sustain 75% of them due to osteoporosis and smaller baseline muscles, and it’s the reason why 20 to 30% of adults over 70 die within a year of a hip fracture, and up to 50% never regain pre-fracture independence.

This is precisely why Attia calls muscle “health span insurance”. It’s your buffer against catastrophe and enhances recovery after a fall. Immobilization losses, including bed rest, can cause up to 1% muscle loss per day in older adults. After the age of 75, as I mentioned earlier, many individuals are unable to fully regain lost muscle mass, resulting in chronic weakness, frailty, and a cascading effect on their independence.

One fall leading to hospitalization can lead to deconditioning, which in turn increases the risk of falls and may result in repeat falls. It becomes a vicious cycle. Muscle plays a protective role, and with each standard deviation increase in leg strength, there is a 30-40% reduction in the risk of falls among older adults. Higher muscle mass is independently associated with a lower risk of fractures, even after adjusting for bone density.

Resistance training reduces fall risk by 30 to 40% in randomized controlled trials, particularly in multi-component programs that incorporate both balance and strength training. The bottom line is that muscle is fall protection; more strength equals more balance, which equals lower risk. Falls are lethal, and hip fractures equal 25% one-year mortality. Many never regain independence. Prevention is leveraged. Building and maintaining muscle now is your best defense against muscle loss. It’s literally fall insurance.

Closing thoughts for my readers:

If you’re healthy and over 50, you have no excuses. Take advantage of your healthy seasons — you never know when an accident will come. Build resilience and reserve now, so if you face downtime, you have strength to draw from.

To echo Dr. Attia, think of your strength and muscles as a glider. The higher it’s towed into the sky, the longer it stays aloft. The more muscle mass and strength you carry into your golden years, the longer and more fulfilling your descent — until the good Lord takes you home.

Further Reflections

I began this post with my story, but I’ll end with one far more personal — my Mom’s.

She had her first back surgery in 2014 at age 68. Since then, she’s endured twelve major back surgeries and one shoulder surgery. Looking back, I can see the steady decline after each operation. It’s a sobering example of what repeated immobilization and disuse do to the body. Older adults can lose 10–15% of lower-body strength in just 10 days of bed rest. Multiply that by 12 surgeries — my Mom hit rock bottom in September 2024.

Her mother, “Nanny,” passed on August 31, 2024. The afternoon of Nanny’s funeral, my Mom’s husband, Chuck, suddenly died. Layered on top of her pain, it nearly broke her. Weeks later, her body shut down — she lost the ability to walk. It was as if someone pulled the power cord from the wall.

She’s been confined to a wheelchair for the past year, living between bed and sofa. She still does PT 1–2 times per week, and it helps, but the prognosis isn’t good. My Mom never strength-trained, so she had no reserve when the first surgery came.

She now exhibits the hallmarks of frailty syndrome: weakness, exhaustion, low activity, and dependency. Once established, frailty predicts a shorter lifespan and greater vulnerability to hospitalization. Extended sitting accelerates decline dramatically. For adults in her position — late 70s, multiple surgeries, dependent on caregivers — average life expectancy drops to 2–5 years. Some hold on longer with loving care and stability, but others decline suddenly after an infection or another fall.

Yet despite everything, my Mom is still here. Still fighting. Still showing up. That’s resilience.

At this stage, my goal isn’t about adding years — it’s about enriching the time she has left. Reducing pain. Maximizing dignity. Keeping her connected to people she loves. Protecting her from further trauma. Every day she’s here is a gift — a chance for connection, love, and grace.

Without a miracle turnaround, she’s nearing the end of her story. My mission now is to be present — whether in person or through technology — to make her feel valued and seen. The compounding effects of frailty make recovery unlikely, but there’s still time for what matters most: love, dignity, and connection.

That may be the most accurate measure of a life well lived.

Resources:

Your Health is a Five-Legged Stool

Leave a comment